North Peak

Skiing North Peak's Challenging North Couloir

North Peak, California — I want to push myself. It has been a quiet season: a few fine tours, to be sure, but no Defining Moments. That's about to change.

In summer, North Peak's North Couloir is a classic ice climb, requiring ice tools, steel crampons, screws, a rope, and a belay partner. But today, spring snow covers the ice, allowing me to solo the Couloir with skis on my back. Yes—I want to push myself. And today, North Peak will push back.

North Peak is not one of the Sierra's more remote mountains, but it does tend to fall off the map when it comes to notoriety.

I'd never heard of the peak until late this winter, when I saw a report claiming the 'North Peak/Conness Area' had snow. In a year of near-record drought in the High Sierra, that was more than enough to grab my attention.

But North Peak, I soon discovered, is one of those mountains that is conspicuously absent in most California backcountry skiing discussions. In 50 California Ski and Snowboard Summits, author Paul Richins mentions the peak only in passing.

But the mention did peak my curiosity. In the Mount Dana chapter, Richins writes, "The north side of North Peak contains three extremely steep chutes that are popular ice climbing routes in the fall when the snow turns to ice." That sounded interesting.

For more information on North Peak, I turned to a climbing guidebook by John Moynier: Climbing California's High Sierra. Moynier provides a healthy section on the Mount Conness area. He describes North Peak's north couloirs as Class 4-5 ice climbs. For skiers, he adds, "These gullies also present excellent extreme ski descents in the late spring."

It was hard not to notice both authors were labeling North Peak's skiing with a word they did not toss around lightly: Extreme. I didn't know whether or not North Peak's north gullies deserved the use of the always-controversial E-Word, but I knew a way to find out. I began packing my gear.

Tioga Pass Road

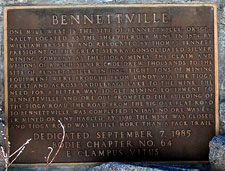

When Highway 120 and Tioga Pass are open, accessing North Peak is a marvelously simple affair. Tioga Pass Road was built in 1883 to support the mining town of Bennettville, which sprung up abruptly when thousands were lured to Tioga Pass by reports of a rich silver lode.

The Road is an impressive example of human effort—and folly. Bennettville's investors neglected to verify that silver actually existed in the hills. No ore was ever mined, and less than ten years later, Bennettville and the mine vanished. Still, we have the unfortunate miners to thank for the existence of Tioga Pass Road.

The road is the only transverse route across the High Sierra, cresting nearly 10,000' at the Pass. To drive the road in Summer is to experience (albeit briefly) the motorized mountain access enjoyed by Colorado skiers, whose state is crisscrossed with roads and passes.

Traveling east to west, Tioga Pass Road takes you past the glorious chutes of the Dana Plateau, past Mount Dana itself, then the fabulous touring of Tuolumne Meadows, before plunging into the heart of Yosemite National Park.

In every respect, the quantity and quality of alpine terrain is dazzling. Mount Conness and North Peak are accessed from Saddlebag Road, near Ellerly Lake.

The semi-paved road takes hikers and climbers to Saddlebag Lake—a mere two and a half miles from North Peak's impressive glacial cirque. For better or for worse, that puts North Peak's technical rock and ice an easy day hike away from the trailhead. Accessing North Peak in Winter is a different story.

The state of California does not maintain Highway 120 in winter. Instead, the road is typically closed soon after it branches from Highway 395, making for a withering 12-mile approach with thousands of vertical feet to gain.

Thus the yearly ritual of California Backcountry Skiers: waiting for the road to open. Paradoxically, it may be better to wish for a poor snow season in the Tioga area. The record snowfall of last year led to an opening date of June 19—well after the best skiing. This year, however, the road is opening on May 11, and I am part of the first wave of tourists, hikers, fishermen, and skiers looking to access Tioga's incredible natural bounty.

Saddlebag Lake

At present, Saddlebag Lake Road is closed. I'm prepared for this possibility: undaunted by my last two-wheeled escapade, I've returned with my bicycle.

It's roughly two and a half miles to the Lake from Highway 120 and Ellerly Lake, where I park my car. Annoyingly, there is just enough snow on the road to make biking impractical, while not being enough to ski. I manage to bike about a mile up the road before I'm forced to ditch the bike in a shrub, and then it's a slow trudge through occasional snowdrifts the rest of the way.

Nonetheless, I'm glad I didn't give up on biking. On a relatively flat road like Saddlebag, the bike makes travel immensely faster and easier.

Though I've memorized the layout of the drainages leading to North Peak, I'm soon confused by the road's eastward drift.

Two and a half miles stretch on and on, and I begin to wonder if I've somehow taken a wrong turn.

But no, it just takes a little patience, and then I see Saddlebag Lake ahead.

As if by magic, the landscape transforms at the Lake's boundary from green, dense forest to a snowy alpine vista.

The sight of so much snow in this year of drought brings a huge smile to my face.

I switch to my skis and free-heel alongside the frozen lake's western shore—no skins required.

This proves to be an efficient mode of travel, and soon enough I'm deep in this snowy wilderness, marveling at its beauty.

The scope of the rolling terrain is overwhelming.

I find myself having to stop and simply gawk at this backcountry skiing wonderland.

With conditions like these, I muse, backcountry skiing actually makes for a decent sport.

As I continue to glide forward, deeper into the backcountry, I can't shake the feeling of how strange it is to be here, alone in the wilderness. It's hard to explain. First of all, I am indeed far from home out here—far from the comforts and safeguards of my daily life.

That distance brings a profound sense of vulnerability. Yet stirred into the mix is also a sense of privilege and gratitude: to be able to do such things, to see such sights. Elemental forces swirl within and without as I continue to press on farther into the wild.

The Extreme Wilderness

Somewhere east of the Yosemite National Park boundary and the Conness Crest is the Harvey Monroe Hall Wilderness Research Area. I say 'somewhere' because maps of the research area are hard to come by.

Please note, however, that overnight camping is prohibited within the research area—wherever it is. Available information suggests the area includes the Conness lakes basin as well as the upper drainage below North Peak—in other words, exactly where the best camping is.

I generally try to obey the rules, at least when it's convenient, so I camp near Greenstone Lake, figuring that will keep me safely outside the restricted zone.

In any case, no angry scientists stop by to kick me out, so I pull off my boots, dry out my socks, and prepare to wait out the night.

It's amazing, looking around, how much good skiing surrounds me. The snow is well-consolidated spring corn with that sparkly-velvet look. I can't believe how smooth it is.

This evidence stands in direct contrast to recent reports I've received about the Tioga Pass area.

Along with the drought came unusual north winds this season. These winds were especially cruel to the Dana Plateau, stripping away friendly snow and leaving only hostile ice and rock.

And so I've been worrying about the conditions on North Peak.

At least based on the immediate area, these fears appear unfounded. I predict tomorrow will easily be the best skiing of the season for me.

I make my camp on a bed of sharp rocks overlooking the frozen lake. It's either that, or camp on snow. I decide to test the rocks versus my Thermarest Pad's durability (note: the rocks win).

As the sun sets behind the jutting rock of North Peak's eastern escarpment, I settle into my sleeping bag, thinking of the day ahead.

What will I encounter in the North Couloir, I wonder?

I vow to be cautious tomorrow. I am traveling solo, after all.

The problem is, I know myself. If something can be skied, I'm the kind of person who'll want to try to ski it. This attitude tends to make for excellent stories and photographs—but it also tends to confer a great deal of risk. In the past, I dealt with that risk in that most common of ways: I ignored it. Now, with more time and experience under my belt, I find myself having transformed into an odd, contradictory creature—an informed extremist, if such a thing exists.

I have come to appreciate how fragile and precious life truly is. This reality is simply not possible to adequately express (but easy, I think, for any father or mother to understand). Of course there is also another, darker truth about life. And this the Extreme Skier instinctively knows: at any moment, life can be snatched away, even while you're sitting comfortably on your sofa. Though this is no justification for taunting the Reaper, it is a potent argument for living rather than hiding; doing what you love, rather than fleeing what you fear.

And between these two irreconcilable poles, I try (not always with success) to find a point of balance without falling off to either side.

Climbing the North Couloir

Thoughts of bears, ice, steeps, and sharp rocks puncturing my sleeping pad make for a restless night. I am much relieved when the eastern horizon begins to lighten.

It is a short climb up the drainage to reach the base of North Peak's impressive glacial cirque. The snow steepens considerably as I make my way up a section of steps to gain the cirque's upper slopes—requiring crampons much earlier than expected. I cross a frozen waterfall-pinch and carefully traverse above the steps, eyeing the growing walls of granite ahead.

Soon enough, I reach the base of the first of North Peak's three couloirs. The left chute has the look of an elevator shaft: exceptionally steep and narrow, with at least two chockstones to contend with.

My objective today, however, is the right-hand chute—the primary climbing route.

When I traverse beneath it a few minutes later, the perspective looking up the chute is so warped I can't get a sense of its steepness. It doesn't take long to remedy the problem.

Up the apron I go—and the pitch immediately steepens to 45°. I'll check the steepness several more times as I climb. It will never measure less.

The snow makes for good climbing: it's easy to kick steps without sinking too far in. The consistency borders somewhere between winter snow and spring corn—but it's a favorable mix.

Since the Couloir will remain shaded all morning, the snow will be harder than I'd prefer, but still acceptable, given the angle.

Steepness is a funny thing.

I'll admit, I wasn't overly impressed with the view from the bottom of the Couloir. Now, however, the steepness and exposure is beginning to kick into high gear.

I take another measurement. The angle here in the midsection tops 50°. Moreover, the couloir has been climbing slightly leftward, which now puts me over a nasty-looking rock garden two hundred vertical feet below.

To add to the drama, I'm beginning to suspect the upper part of the couloir is blocked by a hidden ice bulge.

I don't like ice. And I don't trust any skier who claims they do.

I understand that ice climbers seek out the stuff like candy. It's what they do. But ice kills skiers, plain and simple. And with that thought, my axe goes THUNK against the ice bulge, and I'm suddenly aware that my crampon points are the only thing holding me onto the hill...

You've been doing fine, my friend, making good progress. The couloir is steep, but your feet sink comfortably into the snow, and your axe shaft plunges deep into firm neve. You feel safe; solid. And then comes that THUNK! Suddenly, your axe won't bite even a 1/4 inch into the hill. Where did all this blasted ice come from? You look down at your feet, and see naked crampon points clawing at clear blue ice. Below that is a yawning void that smiles, says Remember Me? and then drags your stomach clear out of your body and discards it casually on the jagged rocks far, far below.

I carefully, carefully down-climb ten steps or so, until I'm safely back on snow. Now, it's decision time. The ice, as far as I can tell, is blocking the entrance to the couloir. It will not be possible to ski it. Where I'm standing, the snow is steep and exposed. It's a lousy place to try to switch over to skis. I could attempt to down-climb the entire couloir, but this in my opinion would be even more dangerous.

A third option exists: attempt to climb the rest of the couloir via a 55° section of drifted snow bordering the right edge of the ice bulge. Then, either ski down the snowdrift and skirt the ice, or abandon the couloir entirely and descend the moderate south slopes on the opposite side of the mountain.

I resist the considerable allure of simply remaining frozen in place and rehashing the options over and over in my mind. Instead, I decide to try to climb the 55° snowdrift. I'll decide whether or not to ski down when I get to the top.

The Entrance

Tense moments of climbing get to me to top of the couloir, but my plan has worked. By skirting the extreme right edge of the couloir, I've avoided the exposed ice.

The ideal strategy at this point would be to set up a rappel, put on my skis, and rap past the ice bulge to regain entry to the couloir—and the skiable steeps below. I do not have a rope. Already, my experience on the North Couloir is leading to a paradigm shift when it comes to gear.

I won't be skiing chutes like this again without a rope, protection, and—always!—a steel axe.

I thank my lucky stars I brought a steel tool with me on this trip, instead of my usual aluminum axe.

It would be entirely reasonable for me to abandon the couloir at this point and ski the steep but manageable south slopes of North Peak.

But, as I've noted, if I can ski something, I generally want to ski it—and I know I can ski that 55° ribbon of snow alongside the ice.

I give no thought to climbing the remaining Class 3 scramble to North Peak's 12,242' summit.

Nor do I spend much time enjoying the views from the Notch above the North Couloir.

I want to get right to business.

There are a few critical tasks to attend to first: clear the bindings of snow, make sure to snap in securely.

And don't forget to switch the boots to ski mode!

I tighten my pack straps, cinch my boots tighter, and generally sack up.

A short traverse into the entrance, and the fun begins.

My plan is simple: sidestep down the snow ridge and avoid the ice.

For extra security, I sink my poles into my ascent footsteps, effectively belaying my skis' edges in case they slip.

This is a tedious, unglamorous business—and perhaps a tad excessive when it come to caution.

Then again, I'm stepping down a 55° pitch of hard snow, my ski tips inches away from the couloir's rock wall, my ski tails floating inches above bare ice.

I think that qualifies as a no-fall zone. With the help of my ski poles, I safely bypass the ice and sideslip onto the snow beneath.

As expected, the snow is hard but of good consistency for steep skiing. Given all the drama of the climb and the entrance, the first turn feels a little anticlimactic. The pitch is still hovering between 50-55°, however, and that rock garden is still lurking below. While the total vertical of North Peak's North Couloir is a modest 500 or 600 hundred feet from notch to apron top, the chute's sustained steepness greatly expands the difficulty factor.

I work to make smooth, solid turns, carefully leading with a pole plant, following with my upper body, stepping my uphill ski down the hill, pivoting the turn decisively, maintaining balance. Given the hardness of the snow, I'm impressed with the amount of sluff that my turns generate. I stop to let that rushing cascade of snow blow past me.

The couloir's difficulty eases once I've worked my way through the midsection. Now, a fall would only send me tumbling down onto the apron, where presumably I'd come to a rest with no great harm done. Nonetheless, the adrenaline is still flowing freely.

When I reach the bottom third of the couloir, I switch to big, sweeping GS turns that send me roaring out onto the apron, warm wind ripping through my hair. Just like that, it's all over. I stop to take a photo of myself with the couloir in the background. Piece of Cake—if you like yours with extra frosting.

The Way Home

Smooth, flawless corn snow coats the glacier in North Peak's northeast cirque. I'm so delighted with it I ski blissfully past my exit to a dead-end above a cliff band.

That costs me fifteen minutes of hiking back up to escape the Cirque, but I couldn't care less. I'm floating on that jangly rush of endorphins that comes from skiing the super-steeps. Back on track, it doesn't take long to reach my campsite, where I pack up the gear and chow down a PB&J sandwich.

Hmm...are my hands shaking?

After I pack everything up, I enjoy a tranquil tour back to Saddlebag Lake.

I glide alongside the shoreline, steadily putting distance between myself and North Peak.

My first ski tour in the Tioga Pass region has been a doozy—maybe the best skiing I've ever had in the California Backcountry.

Issues of ice aside, the snow has been much smoother than I had any right to expect.

On this weekend, at least, Tioga's rousing steeps and rolling terrain were coated with a velvety layer of spring corn that rivaled the best groomers in-bounds.

And as a final bonus, instead of the usual Southern Sierra dry beater of a hike to the car, I stay on skis all the way to Saddlebag Lake.

Once I hit the road, I'm forced to hike for a mile or so, but then I find my stashed bicycle.

I can't help but grin as I hop on the bike, still in my ski boots, and cruise down the road.

I'm back at my car in minutes, dropping gear all over the parking lot and pulling off my clothes.

A fisherman looks me over and then wades into nearby Lee Vining Creek. I wash my feet in the creek, which earns me a stony stare. Once I've finished washing up, I take a last look at the surrounding mountains.

2007 has been a dry, discouraging season in the Sierra, but what a finale this weekend has been! Tioga Pass did not disappoint—and I barely scratched the surface of this extraordinary region. Immediately to the west is Mount Dana and Yosemite National Park.

This wasn't the year for Dana, unfortunately, but next season can't be too far off. Mount Conness and the Conness Glacier is also waiting nearby. And there are two more couloirs on North Peak's north face worth my attention. Yes, I can see it now: I'll become one of the watchers next year, eagerly anticipating the Opening of the Road. I can hardly wait.