The Opening of Palmyra Peak

Telluride Redefines the Boundary of North American Resort Skiing

Telluride, Colorado — I am standing on Palmyra Peak's summit ridge with two Telluride ski patrollers, and they seem every bit as amazed as I am to be here.

From our perch at 13,150 feet, we can see deep into the vast high-altitude cirques and spines of the Telluride backcountry—Lena Basin, San Joaquin Ridge, Bear Creek Canyon. But we are not chasing backcountry turns today: we are here for in-bounds, avalanche-controlled skiing. Palmyra Peak is open for business, and the magnitude of that reality takes our breath away.

'Quirky' is a word that pops up again and again when people try to describe Telluride. Unlike the majority of Colorado's megaresorts, Telluride was built for miners, not skiers.

Telluride began as a mining boomtown—by all accounts a hell-raising place where miners toiled in the treacherous hills above and spent their meager wages in the abundant brothels below.

When the mines eventually dried up, the town shrunk to near-extinction. Then, in the 1970's, hopeful locals persuaded an entrepreneur to put in a few ski lifts.

If anyone was expecting sudden prosperity ala Vail or Aspen, they were surely disappointed. The shady, heavily-forested north slopes over town were much too steep to build the green and blue groomers so beloved by Colorado resort skiers.

Additionally, Telluride's southerly latitude made for a quirky, cranky snowpack. Coverage was typically poor during the critical holiday weeks, and avalanche danger typically high all season.

And then there was the issue of access: it was easier to drive to Telluride from Phoenix than it was from Denver, which effectively separated the ski area from its most important market.

Liabilities like these would easily have sunk most ski resort ventures. But while Telluride didn't conform to the usual Colorado template, it did offer things the rest of the state could not begin to match—like the Plunge and the Spiral Steps. When my family and I drove to Telluride from nearby Flagstaff Arizona in 1983, the two runs were already legendary for their big vertical and their steepness.

My brother and I might have been kids, but that didn't stop us from heading right for the top of the mountain to test ourselves against the very best Telluride had to offer. It took an abominably-slow four chairlifts to get to the top, but skiing the Spiral Steps for the first time that year was undoubtedly one of the formative events of my young ski career.

In addition to expert ski terrain, the young Telluride resort's other signature quality was its unequaled views. Set deep in the confines of a box canyon within Colorado's San Juan Mountains, Telluride evoked the grandeur of a tiny Alpen village rather than the more austere landscapes of the state's Central Rockies to the north.

Still, after a week of skiing, we were ready to go home. Even young chargers like my brother and I got tired of the resort's bump-heavy terrain. And riding four lifts to get to the top grew progressively more annoying with each day. The views were glorious, yes, but staring at all those fantastic peaks and couloirs just beyond reach took its own kind of toll.

Day after day, it only served to reinforce exactly how incomplete the mountain was. If you were a skier, you could see in Telluride the outlines of a potential resort almost too wonderful to imagine. But who would ever build it? Telluride seemed firmly fixed in its quirky blend of potential and problems, and in 1983, we saw nothing to suggest that would ever change.

Split Personality

We might not have seen change coming, but others in and around Telluride clearly did, and that set off a conflict that would last for decades.

To residents of the tiny town of Telluride, it was becoming evident they'd found a Shangri-La of sorts. Telluride offered world class skiing, ice climbing, and mountaineering without the high prices and pressures of a megaresort growth curve.

But there was more to it than just that. A home-grown, funky culture was blossoming in Telluride. It wasn't just the usual Bohemian experiment: it actually seemed to be working.

To many residents who loved Telluride, it was clear they'd found something special—and something fragile.

Something worth protecting.

A few years after my first visit, I returned to Telluride for a college ski trip. The mountain had added a few chairs and realigned a few others.

They had also begun aggressively grooming some of the resort's steepest town-side runs.

The impact was huge. Adding groomed expert terrain was a stroke of genius that more than compensated for Telluride's lack of groomed blue runs.

And even that deficiency was in part corrected with Chair 10, a lengthy high-speed quad that opened up miles of beginner and cruiser terrain.

Chair 10's greatest impact, however, had little to do with skiing. The lift opened up a vast resource critically absent in Town: land.

While the town of Telluride was engaged in a fierce war with developers over the future of the wetlands at the valley's entrance, Chair 10 in one master stroke rendered the argument moot.

The billionaires' mansions and resort hotels would come to Telluride after all—but they would be built on the opposite side of the mountain. Thus was born Mountain Village—the town's posh alter ego. It was a victory of sorts for both sides. Town residents managed to stave off the explosion of development they feared would destroy their community—at least, within the Telluride valley's walls. And developers at last got to cash in (hopefully) on Telluride's rich potential as a destination resort.

Before the town and village's schizophrenia became too pronounced, the town wisely invested in a free gondola which made for an effortless commute between the two sides. In practice, the gondola—and the split—proved to be a relatively elegant solution. Both Telluride Town and Mountain Village benefited from the other's existence without losing their own specific identities.

Ultimately, there was no question that change—and growth—had arrived in Telluride, both on and off the mountain. No one was going to confuse the ski area or its split community with Vail, or Aspen, or Snowmass, but it was clear the genie was out of the bottle. Skiers and residents had ample reason to be both excited and apprehensive as to what was going to come next.

The Telluride Backcountry

Despite the changes taking place in town and Mountain Village, one thing in Telluride remained the same: the ski terrain was relatively limited.

For in-bounds skiers, Telluride was a big mountain that somehow felt small. Unlike other Colorado resorts, you could easily blow through most of the hill's runs in a day—even a morning. There was the town side, the village side, and Chair 10.

There was also the huge expanse of backcountry terrain beckoning just beyond the resort's boundary, but Telluride's backcountry was a story in itself.

For those who knew how to access it, the San Juan backcountry was about as wild as it got in Colorado.

It was also dangerous, and, from the perspective of liability-conscious government and ski resort officials, much too easy to get to from the resort.

Telluride's entire east face was closed terrain.

From the top of the well-named See Forever ski run, countless tempting chutes dropped just beyond the orange rope into the glorious but cliff-banded Bear Creek Canyon.

It was obvious, looking down these plunging elevator shaft lines, that these were not chutes for the average resort skier, but that didn't seem to stop people from getting killed trying to ski them.

And thanks to Telluride's shallow, ill-tempered snowpack, much of these northeasterly lines offered hair-trigger avalanche danger throughout the season.

Telluride Patrol and the Forest Service responded with an aggressive policy of closure.

Even during our 1983 visit, it was obvious that Telluride was exceedingly conservative when it came to opening terrain.

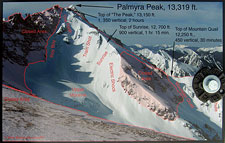

Too conservative, in our young opinions. We could forgive them—maybe!—for the Bear Creek closures. We were young, but we weren't that stupid. But in the opposite direction, the equally glorious Prospect Bowl and Palmyra Peak were also closed, and that seemed downright ridiculous.

Yes, as I returned year after year and grew a bit more seasoned, I came to notice the perpetual fracture lines and slide debris that decorated Gold Hill.

But it remained hard to fathom why one unstable ridgeline kept so much intermediate and expert terrain off-limits. Yes, Telluride eventually opened (occasionally) a backcountry access gate, and even a few limited hike-to skiing opportunities from Gold Hill. But the original problem remained: skiing Telluride, I found myself looking at achingly-near out-of-bounds terrain that begged to be skied, but remained stubbornly closed.

The Prospect Expansion

Between 1999 and 2001, Telluride entered another period of expansion, spurred by a change in ownership. Sony executive Joe Morita became a majority share holder, and he infused the resort with cash.

The rumor was that Morita had fallen in love with Telluride and wanted to turn it into his personal playground, cost be damned. True or not, it is a revealing story. In terms of the bottom line, Telluride was surely never a ski resort that made a whole lot of sense.

One of the resort's signature qualities is its striking lack of crowds—even on weekends. That might delight weekend skiers, but it hardly makes investors happy.

To round out its patchy on-hill experience, Telluride absolutely needed a big influx of cash.

But who would be crazy enough to spend it? It was impossible to imagine an effective return on the investment.

Whatever Morita's motivation, his money helped correct two of Telluride's most glaring lift deficiencies, by replacing the awful Village and Palmyra Lifts with high speed quads.

Next came the most significant expansion of skiable terrain in the resort's history: the addition of the Prospect and Gold Hill Quads.

The Gold Hill Quad sat right in the middle of Telluride's on-again-off-again hike-to terrain, opening the heart of it to lift-served skiers.

In one fabulous five minute ride, the Gold Hill Lift boosted skiers 1500 vertical feet to the 12,255' top of the ski resort, from which they could drop numerous double blacks 'till their legs fell off, or retreat and enjoy the scenery en route to the Village via See Forever's rolling blue terrain.

With Gold Hill open, even on powder days, the face of Telluride had changed yet again.

And for once, there was now a bit of a happy dilemma when new snow fell and it was time to choose where to ski. Gold Hill gave Telluride skiers a new-found abundance of options. Riding up Palmyra Peak's northwest ridge was the brand-new Prospect Lift. Here, skiers found a wealth of much-needed intermediate terrain tucked right underneath Palmyra Peak's imposing north face. It might have seemed impossible, but the Prospect Lift significantly boosted Telluride's already spectacular views.

Many skiers—myself included—hop off the end of the Prospect Lift and find themselves thunderstruck by the overpowering presence of Palmyra Peak towering above. It is a sight unlike anything else in Colorado, made all the more intense by the sheer proximity of the Peak's serrated ridges and fluted buttresses.

When my family and I returned to Telluride to ski the new terrain opened by the Gold Hill and Prospect Lifts, it felt much as if we were visiting for the first time. As a ski resort, Telluride had at last realized its potential. The mountain had arrived.

Palmyra Beckons

Given Telluride's history of closing avalanche-prone terrain—and keeping it closed—it wasn't surprising that Palmyra Peak was off-limits to skiers.

Yes, resorts were rushing to open challenging terrain to attract 'Freeride' customers. But Palmyra Peak was not the usual American dabble in steep skiing. In all directions, Palmyra offered exactly the sort of cliff-bound terrain that got ambitious skiers killed with clock-like regularity in France's Chamonix Valley.

Add to that the peak's significant avalanche issue, which could threaten intermediate and beginning skiers in Prospect Bowl below, and you had a potential liability nightmare.

Surprisingly, plans did exist to open Palmyra Peak to skiers as part of the resort's controlled terrain.

Still, skiers had reason to be skeptical.

Many resorts offer big expansion promises that never seem to materialize.

But more than that, it was difficult to believe that a resort as historically conservative as Telluride would ever open such radical, next-generation terrain.

Even for perpetual dreamers like myself, it seemed just a little bit too much to hope for.

After all, in terms of in-bounds skiing, there was really no precedent in North America for anything comparable to Palmyra.

If anything, the most likely possibility was that Telluride would 'open Palmyra' by permitting limited access to the peak's lower terrain. And, eventually, that's exactly what happened. The Prospect Expansion allowed a tiny chip of skiing off Palmyra Peak's northeast ridge, in the form of a few very short, hike-to expert lines—Confidence, Crystal, Genevieve.

A few long years later, access to the excellent skiing beyond these runs—the Mountain Quail Couloir and Black Iron Bowl—was opened, but only to 'guided' parties. That allowed Telluride to claim that Palmyra Peak was open for skiing, but only in the most limited possible sense, and only if you were willing to pay a steep fee on top of your already-pricey lift ticket.

Telluride repeated the 'New Palmyra Terrain' mantra in preparation for the 2008 ski season, but by this time, it was beginning to sound to me like the boy who cried wolf. I looked over the 2008 trail map and saw a 'closed' line that looked to be in the same place as always. The best I figured I could hope for was that the annoying Guide-Only requirement had been dropped. Otherwise, I expected the Palmyra story would remain the same.

Black Iron Bowl

It's easy, looking at a 2008 Telluride trail map, to dismiss Black Iron Bowl as a trivial addition to the mountain's in-bounds terrain.

That area had never particularly been on my radar. To the best of my recollection, Black Iron Bowl was pinched between an intermediate run and a cliff band, and consisted primarily of a dreary gully funneling back to the Gold Hill and Prospect Lifts.

So when I heard Telluride was claiming they'd opened Black Iron Bowl and (once again) Palmyra Peak, I was curious to see what, exactly, was new.

But my expectations were somewhat diminished after years of Telluride teasers. I certainly didn't bother bringing any climbing or backcountry gear.

In retrospect, Telluride's new additions change the face of the resort so much it takes time to get used to them.

When my brother and I arrived in town for a visit, we couldn't have picked a better time.

Standing in line at Chair 9, I overheard a ski patrol joking he'd have to retire—because conditions were never going to be this good again in his lifetime.

2008 brought both record snowfall to Telluride and a remarkably stable snowpack—a dream season for opening up new terrain.

We arrived on the eve of a storm that dropped a foot and a half of dry powder across the upper mountain.

Magically, the storm was almost devoid of wind, leaving only smooth, slabless snow that was the delight of skiers and patrol alike.

Black Iron Bowl was open by 10:30 a.m.

It's funny to say, but we were almost reluctant to make the trip over to the Prospect Lift and hike up to Mountain Quail. Skiing was so good elsewhere on the mountain that hiking to unknown terrain seemed almost like a bad bet. It didn't take long, however, for my brother and I to realize we were about to drop in to some of the finest powder terrain we'd ever skied.

How good is Black Iron Bowl?

Call it helicopter skiing without the chopper. A healthy 450 vertical foot hike (about 30 minutes) got us to the top of 'Mountain Quail', the oddly-demure name for the steep, broad couloir that drops into the heart of Black Iron Bowl. From the top of the couloir, I stared down at the spectacle of untracked glory below as if it were a mirage.

In that moment, I was no longer in Telluride. I was in a skiing fantasy land where even my wildest dreams were beginning to seem modest in comparison. Untracked resort powder as far as the eye could see! Huge, gorgeous lines plunging down through some of the most scenic terrain imaginable.

We dove in and chased each other down the mountain. It was overload, pure and simple. Did anyone else in Colorado know about this?

Climbing the Ridge

Palmyra Peak is open. I'm in Alpine gear and I don't even have a backpack, but I'll carry my skis to Hell if I have to for a chance to ski this peak.

Moments like these are rare in life, I find. History is on my mind as I ride the Prospect Lift to the start of the hike—over twenty years of skiing Telluride and dreaming of this very day, right now, right here. I try to quash fears the gate will close early.

Just get me to that gate on time, I pray. Give me my chance. No one wants to climb this mountain more than I do today. At the top of the Prospect Lift is a big sign marking the various routes down Palmyra Peak.

Call it a road map for radicals.

According to the sign, the climb is 1350 vertical feet and two hours—if you want this, you'll definitely have to earn it.

And that climb is perhaps big enough to help weed out those whose ambition outweighs their judgment.

I kick-step my way past a gaggle of skiers en route to Black Iron Bowl's earthly delights.

When I reach Mountain Quail, I'm the only one continuing higher, and the gate to Palmyra Peak—thank god!—is open.

Now, before we begin, maybe we should take a little reality check.

I'm in my alpine gear here: heavy Lange L10 Racing boots and Atomic R11 skis draped over my shoulder.

Aside from my stylish Smith Factor sunglasses, at the moment I'm not especially well equipped for big mountain adventures.

Up ahead is 1350 vertical feet of climbing up an exposed high-altitude ridgeline, some of which entails a least a smidge of dicey rockwork.

There is no gatekeeper here—no one to tell you you're not geared up properly, or fit enough, or crazy enough to ski this kind of terrain.

You'll have to make that decision yourself.

My take: don't try to start your adventure ski career here.

There are plenty of steep thrills to be had on Mountain Quail and Black Iron Bowl below, and there's plenty of danger to be found as well, if that's your game.

As an added bonus, Telski Patrol will have a much easier time picking up the pieces if something goes wrong.

In any case, retreat is a poor option above.

Once you start climbing, you will soon be committed. Up the spine I go, finding patchy coverage on loose, rocky ground as I work my way up the spine of Palmyra Peak's northeast ridge. Crampons would be nice here. So would my A/T boots and skis—and especially a backpack to carry them.

My trusty but very hefty alpine boards are printing deep bruises on my shoulders, with much more climbing to come. I time my breathing to my steps and push the pace a bit, trying to catch a group of skiers far ahead.

As I gain altitude, the sense that I am in or even near a resort vanishes. In fact, if I feel alone up here—which I do—it's because I am. Soon, there's no one else in sight, just majestic views of strikingly sheer rock and snow, and the immense sweep of the valley below.

As a backcountry skier, I'm used to solitude. But the abruptness of this transition from managed resort to untracked wild is a little disconcerting. It's hard to fit this experience into my (prior) conception of Colorado resort skiing. By at last expanding to include Palmyra Peak, Telluride has elevated itself to a level of skiing previously unknown to major North American resorts.

Elevation

On their own, either Palmyra Peak or Black Iron Bowl would have been transformative additions, but it is Palmyra that makes the boldest statement.

When I crest the northeast ridge, I find the final few steps to Palmyra's summit are closed, preventing an exact summit ski descent. I deduct the appropriate amount of style points, but the meter remains pegged. Hyperbolic adjectives flow steadily through my head as I contemplate my unlikely perch.

From the top of the Prospect Lift, elevation 11,815', it has taken me exactly 50 minutes to reach the top of 'The Peak'. As a sea-level Californian (currently!), I feel satisfied I've done an adequate job representing the West Coast.

Self-satisfaction aside, it's time to examine the options.

Essentially the entire northeast face of Palmyra Peak is open for skiing. The main route drops right down the middle, steep enough to roll out of view, big enough to give me the jitters.

It's therefore comforting to discover the climbers I've been chasing up the hill are two Telluride ski patrollers.

I stop for a quick chat.

First I have to congratulate them on their mountain's glowing new addition. It's obvious they're every bit as excited as I am.

Telluride tries to keep patrol teams continuously rotating through the new terrain. In practice, that means help is never too far away, though it's by no means immediate. Telluride hopes to keep Palmyra open as regularly as its other hike-to areas, conditions permitting, rather than as a rarity.

That would be nice—but it's also far from certain.

I think it's fair to say that Palmyra Peak is an experiment of sorts. The work involved in assessing and controlling this vast, steep peak's terrain is no doubt considerable.

And the stakes are high.

One could easily imagine a few high-profile accidents or mistakes occurring here that would soon convince the powers-that-be that keeping Palmyra open is more trouble than it's worth.

Or perhaps what will undo Palmyra will be the snow. A few bare or sketchy seasons could be the end of the experiment as well.

And so, as I drop in for the very first time, I do not take for granted that this will be a regular part of my Telluride visits from now on.

Crust bits and powdery sluff cascade down around me as I make cautious turns on the steep upper headwall.

The pitch is steep—around 45°—and quite sustained all the way down to the cirque some thousand vertical feet below. The quality and depth of the terrain is mind-boggling. Over the years, Telluride has become masterful in tailoring itself to match its skiers. It is possible for beginners, intermediates, and experts alike to believe the mountain was made especially for them. To that list you can now add the ski mountaineer, for Telluride has looked far beyond the interests of the typical resort expert with the Palmyra addition.

When I enter the cirque, the terrain opens up into a broad expanse offering untracked powder in all directions. This is effortless, intermediate terrain, a fine treat after the 'EX' rating above. I stop, along with the ski patrol I've been shadowing, to survey the vast snowy peak behind me.

It will take time, as I've said, for word to spread about Telluride's new additions. Hearing about it, people will naturally assume it is not much different from what they've found at other resorts. That's probably okay with the locals. If you're meant to be here, you'll find your way. If not...well, there are plenty of other ski areas to choose from.

The Milk Run

And so we come to that part of the story that I hate most of all: the end. For me and my family, this year's wonderful week at Telluride is almost over.

I find my annual trips to Telluride have become a sort of giant clock, ticking off the passage of another year with inarguable finality. Once upon a time I took for granted that there would be an unlimited supply of ski vacations to look forward to. Now, alas, I know their number is limited.

The Gold Hill Lift whisks me to the top of Telluride for what will be the last run of the day. We'll take See Forever to Milk Run to town, and then it will be time to pack up for the long road home.

The upper part of See Forever tracks the ridge atop the mountain, offering signature views to either side of the divide.

From the upper narrows—a catwalk, really—See Forever merges with Chair 9's traffic, becoming a freeway of rolling, open terrain perfect for ratcheting up the speed.

The wind rushes in my ears as I carve big GS turns down the face, then tuck my arms back for the flats through the trees ahead.

Is there time to make a last ride up Chair 9?

Probably not. I speed past the Lookout sign and race down See Forever's open section above the Gondola. Watch for the slow signs at the bottom; burn off that extra speed before the merge.

I cross under the Gondola to Milk Run—my favorite pitch on the mountain. If you ask me, catching Milk Run groomed first thing in the morning is about as good as life gets on skis. Now, the run is chopped and melted, so I shift to slalom turns, using my hips to push those edges into the hill. Town is getting closer. I take the lower part of Telluride Trail at the merge, entering the last funnel before the final pitch of the day, where I stop to survey the town of Telluride below.

Much has changed since my 1983 visit, in ways both good and bad. As a ski resort, Telluride has unquestionably found the missing pieces of its quirky puzzle, but for locals especially, the shift from aging mining town to world class resort has not come without a price. Still, the magic of the place remains intact, somehow.

I push through the last bit of skiing to the bottom of the hill, skid to a stop at the base of the Gondola, pop off my skis, and just like that, the giant arm of my Telluride clock shifts another notch. Will I be back next year? I sure hope so.