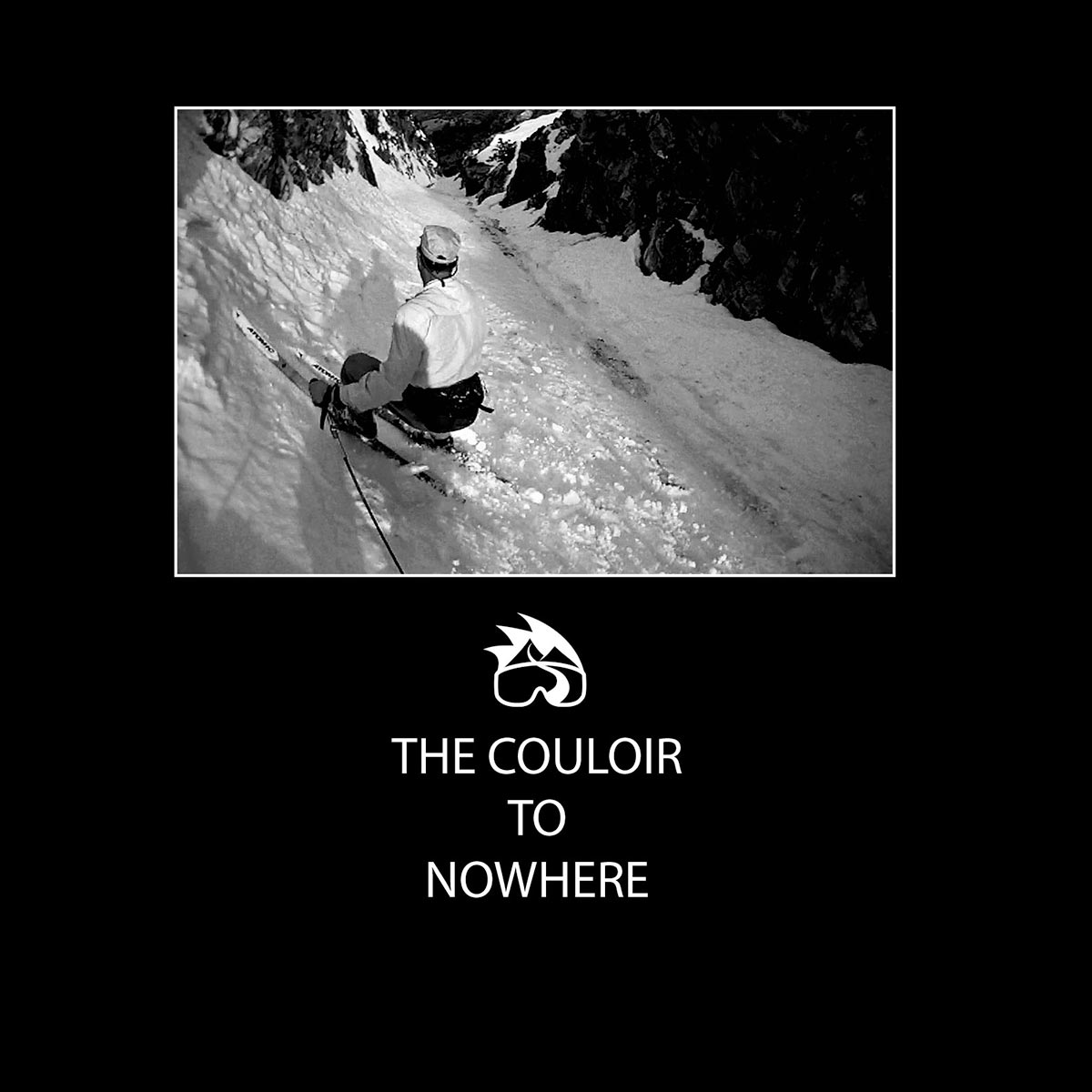

The Couloir to Nowhere

A Southern California Ski Mountaineering Adventure

Los Angeles, California — I first saw it in January 2008. My friend Bill Henry and I were climbing Baden-Powell for a modest day tour in Southern California's San Gabriel Mountains.

As we stood on the summit and looked across the deep chasm to our south, we noticed a pencil-thin couloir shooting down an unknown peak in the distance. The line looked steep, remote, and desperate—maybe skiable, maybe not...

When I was a kid, my dad drove us to Colorado nearly every weekend for my brother's ski races.

I went along not to bash gates but to enjoy the skiing at those many fine Colorado resorts—a nice perk of having a USSA-ranked sibling.

I never thought much of it at the time, but today, as a father myself, I'm humbled by the effort my dad put in to get us to those ski races—and to encourage and support my brother's and my skiing.

We spent countless hours driving across the Navajo reservation, often arriving back at our hometown in Northern Arizona past two or three a.m. We'd be at school later that same morning; my dad would be at work.

The drive in either direction was always exhausting. Still, I remember clearly the excitement I felt each time we left home, crossing Four Corners country and entering Colorado and the foothills of the Rocky Mountains.

I would press my face against the glass of our Ford Bronco and watch the mountains rise. And whenever I saw a particularly lofty or inspiring peak, I played a little game with myself: I looked for ways to ski it. I drew imaginary lines all over the mountains of Colorado and Southern Utah from the back seat of my dad's car, and I pictured myself skiing each and every one of them.

It is comforting, all these years later, to know that in many ways I am still that same kid with his face pressed against the glass. I still love to look at mountains. And I still—always—love to look for ways to ski them.

One difference today is that instead of gazing at the summits of the Rockies, or the Wasatch, or Arizona's San Francisco Peaks, I find myself looking instead at the formidable granite faces of the great range to the West—the California Sierra, and the ever-surprising subranges encircling the Los Angeles Basin.

And perhaps the most significant difference of all is that when I see a mountain today, and I find myself looking for ways to ski it, connecting patches of snow from top to bottom, through forests and steeps and cliff bands, instead of just driving on and letting those lines of potential pass forever from memory, I get to stop now and then to take a closer look.

And sometimes I even get to ski them.

Iron Mountain

"A pencil-thin line in the middle of nowhere"

When I first moved to L.A., I viewed the San Gabriel Mountains as a training ground for the Sierra. Nowadays I often wonder if I got that backward.

The first step in attempting to ski that unknown couloir I'd seen from Baden-Powell was determining what peak it was on. Using several photos I'd taken as a reference, I soon identified the peak as Iron Mountain.

It didn't take too much more research to learn that Iron Mountain has a name that suits it perfectly: it is one serious bastard of a hill.

In fact, baring use of a helicopter, it soon became obvious that trying to ski Iron via any aspect was laughable.

Iron Mountain, elevation 8007', is widely considered the most remote and strenuous summit in the entire San Gabriel range.

Iron's north face—the part I wanted to ski—feeds into the headwaters of the East Fork of the San Gabriel River. There is no direct way to access the base of that side of the mountain.

In winter, in fact, the area becomes utterly impassible as the river floods its narrow, winding gorge.

How rough is the terrain?

In 1936 the State of California attempted to build a road from Azusa to Wrightwood through the heart of the San Gabriel Mountains. The East Fork Road project was abandoned two years later when flood waters destroyed the road.

Today, all that remains of that doomed effort is the aptly-named Bridge to Nowhere.

A winter approach from the north was not a possibility.

As for the south approach, to get to Iron Mountain one must begin at Heaton Flat, elevation 2000 feet. Including unavoidable ups and downs, summiting Iron via the Heaton Flat Trail entails a hefty 7200 combined total vertical feet of climbing—one-way. To further complicate the effort, Heaton Flat Trail only goes up to 4800'.

The rest of the approach would involve finding unmaintained use trails that claw their way through thickets of brush. And if that's not enough to get you cackling like a madman, Iron's entire south face can be expected to be utterly bare of snow even in the dead of winter, meaning you'll be carrying skis, boots, and overnight gear (and water—there is no water on the route!) on your back all the way to the summit.

Should you survive that ordeal with some small measure of stamina and sanity left, you've still only reached the top of a ski route that may or may not exist. And if the couloir isn't skiable—or otherwise accessible—well, at least you'll have a heck of a story to tell if and when you finally finish carrying yourself and your skis all the way back down the hill.

If the line does go, remember that however far down the north side you ski you'll need to climb back up. There is no north exit. Once you re-summit, you must then redo the entire south ridge route in reverse.

Daunting, to say the least. As my skiing partner Bill and I contemplated the rigors of such a hellish endeavor, we quickly decided to look for a more palatable option.

San Antonio Ridge

Bill Henry skis above the Los Angeles Basin

From the lowlands of Heaton Flat and the San Gabriel River Valley, our attention soon shifted upward and eastward, to the summit of Mount Baldy and San Antonio Ridge.

San Antonio Ridge connects the summits of Mount Baldy and Iron Mountain, which is roughly four and a half miles due west of Baldy. We knew we could get atop Mount Baldy with skis—we did that all the time. Instead of coming up Iron Mountain from below, perhaps it was possible to come at it from above, via the ridge.

It was far from a trivial plan, but it at least had a ring of feasibility about it.

Spend a night atop Baldy's summit, Bill and I decided, then make an early dash for Iron Mountain down San Antonio Ridge.

From Iron's summit, scout and/or ski the couloir, then return back up the ridge to Baldy's summit, ultimately exiting via Baldy's southeast bowl.

Heck, it just might work.

In any case, the plan sounded a lot better than anything else we could think up. So, two weeks after we'd stood atop Baden-Powell, we were back in the San Gabriel Mountains, for the familiar Baldy Bowl-Ski Hut Trail ascent.

Carrying winter overnight loads up from Manker Flat made for a long, slow day. We arrived at Baldy's summit with the sun low on the horizon.

Spotting an opportunity for some sunset turns off the summit, we dropped our packs and skied westward into the setting sun—still one of my fondest backcountry skiing memories.

We spent a chilly night shivering just below the summit in Bill's tent. Unfortunately, when we climbed Mount Baldy's west summit the following morning, we discovered the entire west face was coated in ice.

There wasn't much we could do. San Antonio Ridge is long, steep, and exposed. Covered in ice, with what looked like worsening weather fast approaching, the endeavor had taken a technical turn that neither Bill nor I were ready to tackle. Those sunset turns turned out to be the highlight of the trip. We packed up our camp and headed back down Baldy Bowl to the Ski Hut Trail and the car.

What was frustrating about the effort, in the debriefing room, was that we hadn't really learned anything from it.

Other than discovering that the west aspects of Mount Baldy including San Antonio Ridge can be too icy to ski—which was hardly breaking news—we had no new information as to the viability of traversing the ridge on skis. Nonetheless, that was our only attempt that year. Other objectives captured my attention, and Iron Mountain's north couloir moved to the back burner.

Tense Negotiations

We didn't make any Iron attempts the following year. But, in 2010, an El Nino winter blossomed, offering excellent snow coverage in the San Gabriels.

Once again, we considered and dismissed the Heaton Flat approach. As before, we figured traversing San Antonio Ridge gave us the best chance of summiting Iron Mountain with skis. This time, we eschewed overnight gear, starting instead at Manker Flat at 2 a.m. with the plan being to escape via a car dropped at Heaton Flat in one mighty marathon day.

This time there were four of us—but that number went down to three when Bill decided to turn back at Baldy's summit because of leg cramps.

As for friends Dan, Al, and me, San Antonio Ridge proved icy yet again, but not icy enough to dissuade us from trying to ski it.

From West Baldy's 10,000-foot summit, we made it all the way down the ridge to the low point between Mount Baldy and Iron Mountain, elevation 7200 feet.

Discovering the depth and breadth of the incredible terrain on Baldy's west side was a fine reward on its own.

But our objective was Iron Mountain, and in that we were once again thwarted: a technical section of San Antonio Ridge stopped us in our tracks.

Known as the "Gunsight", we'd hoped to find this part of the ridge covered with enough snow to make for easy passage. Instead, we saw only exposed mixed climbing on crumbling rock.

We looked at it, cussed at it, and shook our fists at it, but none of us were willing to try to climb it with skis on our backs.

And at that moment, who should appear skiing down San Antonio Ridge but Dave Braun, the man who pioneered the Giant's Steps Couloir on Mount Williamson. Dave had learned of our San Antonio Ridge attempt and was chasing us.

Now, I must confess I had a few unchristian thoughts at that moment.

Did Dave know about Iron's North Couloir? I wondered.

Because if he did know our real top-top-secret objective, of all the people in the Great State of California and maybe even the entire planet beyond, I knew Dave was just crazy enough to want to try to ski the damn thing—and more than determined enough to pull it off.

What followed was a coy conversation between Dave and me in which I tried to glean exactly how much he knew about what we were really doing there on San Antonio Ridge without giving anything away.

As for our Iron Mountain attempt, it was obviously over.

We had only to decide now how to get home—and climbing all the way back up to Mount Baldy's summit didn't sound particularly appealing.

Noticing snow leading down into Coldwater Canyon, we checked our map, which seemed to show a trail nearby. And so we decided to go off route, abandoning the ridge, hoping we would eventually connect with our car at Heaton Flat.

For more on how that adventure turned out, please see my San Antonio Ridge Traverse video. Suffice to say, going off-route in the San Gabriel Mountains is almost never a good idea, and it certainly wasn't on this occasion, which involved over 47 creek crossings through fast rushing water in the dark.

Back home and nursing our wounds, there remained the question as to whether or not Dave knew about the couloir we were trying to ski.

He did. He'd seen one of my scouting photos in a group email I'd sent to Al, Dan, and Bill. And of course Dave wanted to ski it. So began a series of tense negotiations conducted via email. I was leaving town for two weeks and feared Dave would try to ski the couloir before I got back. Dave was out of town the following two weeks, and didn't want me to ski it while he was gone, either.

But would the snow hold long enough to wait a full month? Eventually, we made a gentlemen's agreement to wait until the next time we were both available to ski the couloir. The date was set, and with Dave on-board now, I knew there was little question we would ski Iron Mountain's north face—if it was at all possible to do so.

Heaton Flat

Iron Mountain & Mt. Baldy from Heaton Flat

I am sitting beneath a shady tree at the Heaton Flat parking lot, elevation 2000', staring at my skis and overloaded backpack, waiting for Dave and his friend Lou Bartlett to arrive.

With a San Antonio Ridge ski traverse having proven unfeasible, this is the last desperate option to ski Iron Mountain: the Heaton Flat Approach, starting low and deep within the East Fork of the San Gabriel River drainage. The day is hot and Dave is running late.

I'm not really sure at this point whether or not I actually want Dave to show.

Strapping skis to my back and hiking anywhere from here seems like a really bad idea.

Truth be told, I'd be perfectly happy to toss my skis, pack, and gear back into my trunk right now and get the hell out of here.

But no—there's Dave driving up now. Looks like this is really going to happen.

I feel fairly confident in guessing no one has ever carried skis all the way up the south ridge from Heaton Flat. Maybe in some stupendous snow year long ago, someone else might have tried it. But even that seems unlikely.

We greet each other, and I'm introduced to Lou, who is one of Dave's long-time climbing and skiing partners—no doubt tough as nails.

Dave and I engage in a short but spirited discussion regarding whether or not we should carry skins.

I don't think there's any possibility we'll end up using them, and I'm loathe to carry any unnecessary weight. Dave feels otherwise. Lou casts the deciding vote: we take the skins. I still don't think there's any chance we'll use them, but I acquiesce.

It's time: on go those heavy packs, skins included. We leave the paved Heaton Flat parking lot and put our boots to the trail. The awful preflight dread is over now, at least. Now there is only Iron Mountain's massive 7200' vertical to be gained—though I'm trying desperately to ignore that number. Of course we draw stares from the other hikers out and about on this sunny Saturday afternoon.

As we pass we get a steady flow of questions, most of them centered around just what the heck we think we're doing today. We're making a documentary about crazy people, I think to myself. And I'm the lead. But the casual hikers and their questions soon diminish as we get farther from the trailhead. Our pace is probably a bit too fast given the heat. Soon, we're all slicked with sweat, and I begin wondering if the three liters of water I'm carrying is going to be enough to get me to the snow—wherever that is.

I find Iron Mountain's vast vertical distances wholly deceptive. Heaton Flat Trail climbs steeply right from the start, and we've soon gained a solid thousand vertical feet. It's possible, looking at Iron's south ridge ahead, to think we're nearing the summit, but in reality we're still just scratching around the lowlands here. There is so much more work ahead.

Allison Saddle

The heat grows more intense as we gain the top of a long ridge winding eastward. Mount Baldy's snowy west face gleams in the distance, far above us.

Heaton Flat Trail follows the spine of the ridge here, contouring up and down over numerous small summits, forcing us to repeatedly gain and give back the same ground. We are now some 2500 vertical feet above Heaton Flat, heading toward Allison (also called Heaton) Saddle, a low notch that will cost us yet another 300 vertical feet or so.

The trail has become decidedly more primitive. Scrub brush and Manzanita intrudes ever-closer, and soon we are battling an endless gauntlet of overhanging branches that grab our ski tips.

It is absolutely withering.

We dance and jiggle our way through the branches and brush, twisting and turning, dipping and bobbing, trying to free ski tips from brambles only to see them caught yet again.

And again.

The heat is oppressive. Our late start time is punishing us without mercy. It feels like we're carrying skis across a long, hot, bone-dry desert—which, in effect, we are.

The final high point along Heaton Flat Trail before the drop to Allison Saddle begins with a steep climb up a lengthy section of loose dirt. As I start up it, I feel the muscles in both my legs suddenly flutter.

What?

My first reaction is disbelief, followed quickly by profound alarm. We are bouncing around 4700 feet in elevation right now—pitifully far from Iron Mountain's summit. I slow my pace and change the mechanics of my stride, trying to assess what's happening to my legs.

The truth is I already know: my quads are cramping. How much farther is it to Iron Mountain's summit? I mentally run the numbers, quickly calculate the dismal result: there is no possibility I'll be able to make it to the top. And camping anywhere else along this dry, snowless, waterless ridge is out of the question.

Both Lou and Dave are up ahead somewhere, out of sight.

I figure they'll probably be waiting for me at Allison Saddle. As I'm forced to slow my pace to a pitiful crawl to keep my legs in check, I realize I'm going to have to tell them I've got to turn back. I want to believe I'm just dehydrated, that I've sweated out all my salt, but the fact is I'm carrying a crushingly heavy pack on a 140 pound body and it looks like I've just reached my limit.

After all the planning and scouting and effort to get here, the prior attempts, the mishaps and adventures, I am devastated to be forced to give up now. But what else can I do?

The South Ridge

Dave and Lou are indeed waiting for me at Allison Saddle. I walk up, drop my pack, and deliver the bad news: I don't think I can go any farther. From Allison Saddle, the route up Iron Mountain quits the Heaton Flat trail and simply scrambles up Iron's south ridge.

Leaving the trail promises to make the hiking more difficult—steeper for certain, and at least as much brush to contend with. The summit remains at least another 3500 vertical feet higher, not including the inevitable dips and contours.

From head to toe I feel out of it—soaked in sweat, slightly nauseous.

I sit in the dirt beneath the shade of a Manzanita, drinking Gatorade and trying to nibble on some salty foods.

Without hesitation, both Dave and Lou encourage me to try to keep going.

It seems theoretically possible that re-hydrating might put a little life back into my body, but I know there's no way I can match their pace.

However, a nifty idea occurs to us: maybe we can find a patch of snow hidden someone ahead along the ridge. That would allow us to camp below the actual summit—giving me the break I need (maybe) to allow me to keep going.

Dave agrees to scout ahead for snow. Lou agrees to hang back with me, matching my snail pace upward. If my legs hold, I'll keep climbing. If not, Lou will relay to Dave that I've turned back.

It's a plan. And with the sun lowering toward the horizon, and water and food starting to take effect in my belly, I begin to feel a little less wasted.

Dave grabs my skins and stove to pull a little weight out of my pack. Lou takes one of my water bottles. With a lighter load and time for the fluids to work their way back into my muscles, I find I'm able to hold a slow but steady pace upward. My legs feel far from solid, but with careful footwork and pacing, I'm able to avoid that awful fluttering sensation.

To our surprise, the South Ridge affords us a small but much-needed measure of generosity: we find a well-established use trail leading up its rocky spine. Even the tree branches prove a little less snaggy than below, permitting (slightly!) easier passage for us and our ski tips.

Most importantly, with it once again possible that I might actually ski Iron Mountain, I experience a huge morale boost. Still, the success of my second wind effort depends on Dave finding snow well below the summit. I figure I'm good for maybe another thousand vertical feet or so. After that...well, I just really don't want to think about it. Pray for snow!

In the Zone

The sun is low on the horizon and I'm in the zone. Or, more accurately, I'm zoning. Something causes me to abruptly snap out of it, and I'm momentarily disoriented.

Where am I? I wonder. Slowly, I take in my surroundings, discover skis on my back, see that I'm slowly working my way up Iron Mountain's endless south ridge. Ah, yes...now I remember. Still: what the heck am I doing here?

The audacity of this undertaking astonishes me.

And perhaps even more than that, I'm amazed I actually found two other people willing to come along.

I hear Lou and Dave at that moment whooping above me. Dave has found a clean patch of snow hidden on the north side of a dip in the ridge, and is firing up the stove.

We are barely past 6100 feet in elevation, but we've found water and thus our camp site for the night. I shrug off my skis and backpack and set about a serious mission of refueling my spent body.

At our present perch on the ridge we seem to tower over Coldwater Canyon and the distant Los Angeles Basin. Amazingly, Iron Mountain's summit remains nearly two thousand vertical feet higher. The sheer scale of the peak and effort easily recalls some of the biggest hikes I've ever done—Williamson; Tyndall. Iron Mountain gives away little beside them.

The sun dips behind the horizon as we melt snow to make water. The lights of Los Angeles spark to life, filling the darkness below. As the air begins to chill, Dave discovers he's forgotten his sleeping pad. Creative inspiration strikes: Dave asks if he can use my skins as bedding. I'm happy to oblige; after all, he's carried them partway up this hill.

So Dave has been right after all: we did need skins. Though perhaps not for the use he intended. In any case, our skins make for a fine bed for Survivorman Dave, along with some pine needles and brush. As for Lou and I, we prefer the more traditional bedding of our Thermarest pads, and soon we're all at rest, staring at the stars, thinking of the day ahead.

The Final 2K

We're all feeling a good deal more chipper the following morning when the sun makes its way over West Baldy. Summit day has belatedly arrived.

With dinner and now breakfast in my belly, and my body relatively re-hydrated, yesterday's heat and troubles seem like a bad memory. Also driving us now is the knowledge that a mere 2000 vertical feet separate us and our skis from Iron Mountain's summit.

No matter what, we're going to be skiing this mountain today.

Though some question remains as to what exactly we'll actually be skiing.

On the subject of skiing, we've been staring up-close at Mount Baldy's gorgeous west face for two days now—an objective which itself begs to be skied.

Trivia buffs should note this is the same snowy peak and aspect visible in the background of the classic postcard photo of the skyscrapers of downtown L.A. in winter.

True to form Iron's final 2K is far from a jog in the park, but we slowly crunch the vertical up the long south ridge, passing pine trees now instead of just Manzanita.

Lou races ahead and is soon out of sight. Dave and I stay together, snapping photos and marveling at the giant Yucca plants that sprout regularly along our path.

Also notable is the tremendous exposure off the west side of the ridge.

Iron Mountain's entire south face, in fact, is split by a wild cliff-bound gully that strongly suggests our present route may well be the only non-technical way to ascend the summit from any direction.

We reach an open section of the ridge, and the angle moderates. A bona-fide trail appears, offering spectacular views both east and west.

The view I'm interested in, however, is dead ahead: Iron Mountain's summit.

And then I see it: snow.

From the bare rock and dirt of Iron's south face, snow suddenly begins to materialize everywhere, like a mirage in the desert.

I step onto snow and hear that wonderful crunch of ice crystals beneath my boots.

This is not just an isolated patch of snow—no. This glorious white mirage keeps expanding until the entire desert is gone. It's just a few feet higher to Iron Mountain's summit. And with each step, more snow comes into view, as well as the snow-capped faces of the highest peaks in the San Gabriels. I see Mount Baldy, Pine Mountain, Dawson Peak.

And of course I see Baden-Powell rising high above the San Gabriel River Valley, snowy and majestic, the place, three years ago, where this whole adventure was born. We've done it! After the longest, driest, most grueling approach any of us has ever attempted, Dave, Lou, and I have successfully carried skis atop Iron Mountain for very likely the first and very probably the last time in history.

Skiing the North Ridge

Iron Mountain's north ridge does not disappoint. Every aspect suggests danger: steepness, wild exposure, huge rollovers to each side vanishing into the unknown.

I have stared at my Baden-Powell shots endlessly, trying to determine whether it is even possible to traverse the north ridge and gain entrance to the couloir. Now, the ski mountaineering begins: I try to match mental landmarks to actual terrain features, hoping to get us safely past the many obvious hazards between us and our objective.

We begin with the threat of ice.

To either side of the ridge—east and west—lie impressive cliffs we cannot afford to become acquainted with.

So begins a creepy-crawly ski traverse in which each pitch and aspect must be carefully assessed for any possibility of iciness.

I side-slip with my skis right on the apex of the ridge for maximum grip, but I'm soon satisfied that my ski edges are biting. The snow is firm up here, but ice does not seem to be a problem today—check.

Challenge Number Two is potentially a big one: in my scouting photos I've noticed a step along Iron Mountain's north ridge about halfway between the summit and the cliffs above the couloir.

This step appears like it might be passable to the west, but if we can't get around it, our ski day will be a short one. We'll be forced to turn around and go back home.

We work our way carefully along the ridge, heading toward the step.

The views are mind-boggling. I'm feeling a flutter again now—but this time it's in my belly, as the ridge's exposure jangles my senses.

The step does indeed prove to be a bit of a thorny challenge, but it goes to the west, just as I thought it might. A short side-slip down slightly-too-crunchy snow gets us around it with only minimal alarm.

The Third and last challenge entails navigating the cliff bands above and below the couloir's entrance. The key is finding a narrow band of snow that should enter the couloir from the west.

Again, I'm working from memory of photographs taken from miles away, so there is a healthy dose of uncertainty to all this, but after The Step, I find Iron's north face opens up a tad, offering a section of modestly steep trees and glades.

The snow becomes wintry here. I work cautiously around cliff bands seen and unseen, hoping I'm aiming us toward the entrance to the north couloir.

What will it look like, I wonder? An inviting snow-filled gully, or a cliff-bound unskiable mess?

The anticipation is unbearable. So close now.

I hear Dave and Lou talking somewhere in the distance above me. They're a little too far west, I think. I shout up at them, tell them to follow my tracks as I traverse hard right, eastward, toward a promising looking rocky spine. Iron Mountain's north couloir sits within a deep gash, I know, such that it is hidden from view from nearly all angles. That makes finding it now a little tricky.

Also tricky are these ever-present cliff bands. Choose the wrong line, and you'll get hung up atop one of them. I keep traversing, wondering now if I'm leading everyone into one such dead end. But that spine—it looks familiar. As I near it, the view opens up just a touch, suggesting a narrow, vertical gully with snow in it. I think I've found the line. I shout again to Lou and Dave. I think we've found it.

These are the moments that electrify the heart of a ski mountaineer. To be here, on snow, with skis—I don't know how to even begin to describe the feeling.

Iron Mountain's north couloir reveals itself to be a reasonably wide snow gully dropping straight down at least fifteen hundred vertical feet. Somewhere beyond that, the couloir doglegs left and out of sight. From my vantage point here at the entrance, the visible pitch looks to be between 40 and 45 degrees in steepness.

To our north, the horizon is dominated by Mount Baden-Powell—the couloir points straight toward it like an arrow.

We're in the right place.

The snow in the belly of the couloir is streaked with dirt and dotted with rocks. Yes, that famous Southern California sun obviously got here first.

But there is no question now as to whether or not the couloir is skiable: it is.

There is also no longer any doubt as to whether or not Iron Mountain's north couloir will ever be skied, because we're about to do so—right now.

With Lou watching, Dave perches himself right atop the entrance with the camera.

I drop into the couloir.

And...the snow is far from the best I've ever had, but no matter. After all the effort we've put in to get here, this might just be the most rewarding skiing I've ever had—and fun!

We're on a wonderfully steep and narrow patch of snow that drops literally to nowhere, down into the interior San Gabriel Mountains and the San Gabriel River Valley.

The whole crazy enterprise has suddenly blossomed from crank concept to concrete reality.

As for concrete, we are a preposterously-meager 35 miles from Downtown Los Angeles, yet simultaneously about as far removed from civilization as you can get.

On that point a cautionary note: one can imagine the looks on the faces of SAR personnel if we somehow managed to put through a call for help:

What's that? Say again...you're where? No, seriously, where are you? Iron Mountain? Skiing? On the north side? And just what the Hell are we supposed to do about it?

I suppose it might be possible to put a helicopter skid on the summit, but that's about the best you could hope for.

So make those turns with care!

Lou decides to hang back below the entrance to the couloir and watch us, waiting to see if the snow improves when Dave and I get a little lower.

Dave and I continue working our way down the couloir together.

The snow does temporarily get a little smoother in the couloir's midsection. Soon enough, however, the skiing gets choppy again.

Dave and I have a quick pow-wow in which we both agree the prudent thing to do now is to stop where we are and start climbing back up.

But there's a wild grin on both our faces that says we're not quitting 'till we've seen this descent down as far as our skis will carry us.

So onward we go, down, down, and down farther, until we reach the 6000' mark, and the snow at last becomes too soft and rock-pocketed to ski any farther. We're reached the dogleg, allowing us to see around the bend.

The ski descent of Iron Mountain, alas, is over.

But still: Excelsior! We've dropped over 2000 vertical feet down Iron Mountain's north side, in the process surely setting a high water mark in the annals of Southern California ski mountaineering wackiness—as well as realizing a dream that began three years ago atop Baden-Powell's no longer quite-so-distant summit. And look here above us: Lou has apparently decided he wants to get in on the fun as well. I see him making turns through the couloir's midsection, heading steadily lower.

Dave and I exchange congratulations—and I give him a big Thank You as well. Dave's participation, in the end, has proven critical to making this trip happen, and to making it such a blazing success. I was never going to pull this off solo, I realize, and I was probably never going to find anyone else willing to come along, either. As for Al, Dan, and Bill, I find myself wishing they were here now to share this moment of triumph—they're a part of it too, even if it is in absentia.

We fill our water bottles from a spring emerging from the black rock at the Dogleg. Dave asks if I have a name for the couloir. I do. In honor of the nearby Bridge to Nowhere, I want to call this 'The Couloir to Nowhere.' The name captures the feel of the place perfectly, I think—especially as I begin to contemplate the long climb ahead.

Getting home from Nowhere isn't going to be easy.

Once Again, In Reverse

Fast Forward: back on top of Iron Mountain, I find a warm sunny place to rest. Here, I pull off my ski boots and gaze longingly at the impossibly-distant Heaton Flat parking lot.

The 2000' climb back out of the couloir wasn't too bad, to be honest—though perhaps I was fueled by more than a little adrenaline from having just skied it. The hike down promises to be quite a bit less comfortable.

So I think I'll take a moment now to relax, sip some water, and enjoy the view.

If I take a measure of pride in my skills as a ski mountaineer, it is not so much for doing things like skiing 55° descents or taking great personal risks.

I prefer to find challenges that offer at least a tiny bit of wiggle room, in case something goes wrong. We all make mistakes, after all, and even if you don't, you can still get unlucky.

I think what I find most satisfying these days is making unlikely things happen.

It is one thing to envision a line; it is another entirely to go through the process of actually going out and skiing it. In this regard, I was coming to believe that Iron Mountain would forever thwart me.

It has taken a lot of patience and probably a good bit of luck to get to this place today. But it feels good. It feels fantastic.

In addition to elation I must also confess I feel a great deal of relief. This White Whale, at least, is done.

Or, more accurately, mostly done. At some point I've got to get off this log, pull on my hiking boots, heft those skis onto my back, and start tromping downward.

But we don't have to start down just yet—let's enjoy this moment together a little longer. It's funny, but Iron Mountain strikes me as the most team-oriented adventure I've ever assembled. Maybe I really am putting my solo days behind me. Or maybe I haven't fully appreciated how involved others have been in my life, even in those moments when I felt most alone.

Thanks again Dave for being a part of this most excellent trip—and for doing such great work with the video camera. Lou, thanks for keeping me going up that cursed south ridge when I thought my tank had run empty. Al, Dan, Bill—you should have been there. But then again, you were, in a way. Those days we spent scouting San Antonio Ridge provided invaluable beta. And it didn't hurt to get my mental toughness kicked up a notch or two in Coldwater Canyon, either.

Finally, Dad, this one's for you. Thanks for driving me to Colorado, and thanks especially for putting me on skis! I still remember all those trips across the desert in the middle of the night listening to Mystery Theater on KNX 1070 news radio, Los Angeles.

Well, that's probably enough of a break for now. Time to pack up and get these weary old bones back home to my family. I've got pretzels in my pocket, and a full bottle of water on my hip. 7200' feet to the Heaton Flat parking lot? I'm ready...