The Russell Project

Embracing Exposure on Mount Russell's East Ridge

Mount Russell, California — Sierra legend Norman Clyde, who made the first ascent of Mount Russell via the East Ridge, wrote that Russell 'delights the heart' of a mountaineer.

14,088-foot Russell, in the California Sierra, is a climber's mountain, blessed with an abundance of good rock, stirring ridgelines, and sheer granite faces. Having successfully scrambled up the Mountaineer's Route on nearby Mt. Whitney, hikers might expect they'd be ready for Russell.

But not so fast: all of Russell's moderate routes push the limit of the Class 3 rating, passing firmly beyond mere scrambling to actual, exposed climbing.

I got my first taste of this difference on Russell's East Ridge.

The climbing is varied and sustained, with a vertigo-inspiring plunge of over a thousand vertical feet immediately off each shoulder.

It is the unique beauty of this route that the climbing, while challenging, remains legitimately in the realm of the Class 3 rating despite the extraordinary verticality.

Passing along the ridge, it takes only modest skill to move from rock to rock, yet one feels all the thrills of a true Class 5 rock climb, including the ever-present siren of the void below.

Add to this the sublime quality of Russell's rock, and it is easy to understand why mountaineers love the route: it is a heck a ridge.

Upon climbing it solo, I was so moved by the experience I felt compelled to return a few weeks later to do it all over again. To better fix the memories (and better photograph the ridgeline), I decided to recruit a few good climbing partners.

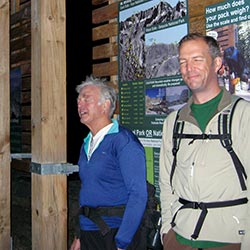

My sales pitch was simple: the route could be done in a day, requiring little more than good scrambling skills and a tolerance for airy vistas. That was perhaps a somewhat nefarious mixture of accolades and omissions, but it succeeded in grabbing the interest of my best friend, Robert, and his father Hugh, an astro-geologist of no small notoriety.

Each of us was no stranger to adventure. As kids, Bob and I had cut our teeth climbing hundred-foot Ponderosa pines in our hometown, against the express orders of our parents. Bob's dad, meanwhile, had more than his share of Sierra climbing adventures in his youth, including an epic North Palisade attempt that sent him crawling all the way down the glacier on his belly to keep from falling through unusually soft snow.

Mixed together with the magic of Russell's austere granite, it seemed certain our eclectic group would guarantee a memorable trip.

Stars and Science

‘Close your Eyes,’ I warn. Pop goes my Casio's flash, commemorating the moment, and we're off, starting from a dark and chilly Whitney Portal.

It's five a.m.

To reach Mount Russell's East Ridge, we will travel up the Mount Whitney Trail and then the lower Mountaineer's Route en route to Upper Boy Scout Lake. From there, we'll quit the popular Mountaineer's Route and instead slog up the long sand and talus of Mount Carillon's South Face, eventually leading to Russell-Carillon Col and the start of Russell's east ridge climbing route.

I make the case for keeping our headlamps off, and Hugh is easy to persuade: without lights, we are able to see the full glory of the stars overhead.

But it is dark on this moonless night, making the footing a little precarious even on the broad expanse of the Mount Whitney Trail.

For this problem Hugh has brought an elegant solution: a red pen light which puts a gentle glow on the trail without tripping up our night vision.

The sky tonight is ablaze with stars—a feast for eyes accustomed to an urban orange mush.

Still, I'm looking forward to the arrival of the sun.

Bob and I debate the relative differential in time between sunrise at our altitude and Lone Pine below.

No slouch in the science department himself, Bob calculates the extra distance to the horizon as a function of elevation.

Moments later, he's deduced, given our present perch of approximately 9000 feet, that we will see the sun exactly thirty seconds before the residents of Lone Pine, CA (if they're watching).

Hmm...that doesn't sound right to either Bob or me.

What went wrong with the calculations, we wonder?

Hugh of course has been lurking in the wings, and he now enters the conversation, deftly noting that Bob has forgotten—Doh!—to account for the fact that the Earth is round.

This is the peril of having a bona fide scientist along for the ride: he or she will with ruthless efficiency pop whatever balloon of an idea you happen to be entertaining at any given moment.

Ah, well, we youngsters can always push the pace a bit, thus enacting some small measure of revenge. The sky begins to lighten as the sun begins its entrance, elevation offset unknown, and we cross back across Lone Pine Creek toward the Ebersbacher Ledges.

I've timed our arrival to coincide with the sunrise, thus assuring we won't be scrambling about on the exposed ledges in the dark. Soon enough we're past the ledges and then past the lower North Fork canyon itself, next stop Upper Boy Scout Lake and places beyond.

Hiking en route to Upper Boyscout Lake

Mount Carillon

From Upper Boy Scout Lake, we part company with the Mountaineer's Route, heading up the steep, sandy slopes of Mount Carillon's Southeast Face.

It is potentially faster to reach Mount Russell's East Ridge by continuing directly up the drainage above Upper Boy Scout Lake, though this route is perhaps more rugged. Either option demands considerable patience, however, as one soon confronts a relentless 2000 vertical feet of hiking up loose, sandy ground.

Also a factor now is altitude. Having passed Upper Boy Scout Lake, elevation 11,300', we lowlanders are starting to find the air a bit thin.

Ironically, fitness can work against you when it comes to coping with high altitude.

A physically-fit climber's respiration rate tends to react more slowly to the thinner air, unlike the instant gasping of a couch potato.

But 'over-breathing' is exactly what the body needs in this context in order to maintain oxygen saturation.

Savvy hikers can consciously work to counteract this liability by timing their breathing to their steps, and breathing in more deeply and rapidly than they think they need to.

This technique can be quite effective in fending off AMS symptoms, though it is of course far from perfect, and comes with its own risks, including hyperventilating.

Hugh dubs this part of the climb 'the Grind'—and Carillon's talus is soon grinding away at all of us.

In terms of distance, Mount Carillon's 13,552' summit is but a short detour on the way to the East Ridge.

Our scientist, however, is beginning to show signs of fatigue, so extra climbing will not be on today's agenda.

I try my best to stay on solid ground as I ascend, but it's impossible not to slide backwards with every other step on this ever-shifting landscape. We stop to rest, then soon stop again for a snack.

We're not far from Russell-Carillon Col, I say, trying to sound encouraging. But the Col is nowhere in sight, just more talus and sand. I know Russell's East Ridge will spring into view soon enough, offering a preview of its electrifying climbing, but first we have to get there, and the only way to accomplish that is to earn it.

Apprehensions

The delights of endless talus must, eventually, come to an end, and so after many rest stops and much grinding we crest the chute we've been slogging up.

Enter a refreshingly flat section on the south flanks of Carillon, reminiscent of Langley's sandy high-altitude 'beach'—and enter the East Ridge.

Mount Russell's East Ridge springs abruptly into view, offering a preview of adventures soon to come. At first, we are only able to see Russell's southeast face, which is of course a sheer drop of vast distance.

As we traverse beneath Mount Carillon's summit, however, we are gradually allowed to see the opposite side of the East Ridge.

The north side of the ridge appears to be a smooth slab of granite that rolls ever so elegantly off to infinity.

Some have described it as a giant bathtub rim.

As an alternative metaphor, imagine a massive, impossibly-steep wave that is in the act of breaking.

The back of the wave rounds smoothly at its apex but plunges downward ferociously, soon reaching an angle of 90°.

The front of the wave seems to arch over itself, the lip a tangled mass of gleaming Sierra granite caught in the act of beginning to curl.

Now make that wave 1800 vertical feet high.

With each step, Mount Russell's East Ridge seems to grow steeper and narrower, hyper-real, as if someone has dialed up the vertical exaggeration in Google Earth to make the image pop.

And—best of all—I and my companions are now contemplating that ridge, wondering how on Earth we're going to climb up it with only hands and feet and nerve.

Words and photos will only go so far here: this is one heck of ridge.

The sight brings a certain nervous energy to our endeavor—a veil of apprehension swirling about the subconscious. Not much farther, we gain the saddle of Russell-Carillon Col, elevation 13,260'. Peering over the edge of the ridge here treats us to a view of Tulainyo Lake, which at 12,825' is the highest permanent lake in the United States.

We are also afforded the opportunity to contemplate the route ahead, which looks quite frankly to be utterly impassible without technical rock climbing equipment. Hugh and Bob eye the ridge doubtfully as I point out the seemingly-minuscule crack system we'll follow along its exposed north slabs.

This is part of the genius of the East Ridge: despite its formidable appearance, it is indeed a Class 3 route—at least in terms of actual climbing difficulty. But be advised that Class 3 rating doesn't tell the whole story, as I and my companions will soon discover.

The Climb Begins

The terrain on Mount Russell's East Ridge is surprisingly varied, with dramatic but ever-changing sections that always keep you guessing as to what's coming up next.

The climb begins as we leave Russell-Carillon saddle and begin scrambling up steep talus blocks. This short section is pure scrambling, mixed with anticipation. We've been staring at Russell's spiny ridge for some time now—will a reasonable route materialize?

The talus makes for a welcome warm up.

Soon, however, the ridge's steepness, narrowness, and exposure steadily increase.

Also increasing rapidly is our elevation, and with it the impact of the view off either shoulder.

Suddenly, it feels as though we've jumped atop the back of a giant Stegosaurus.

The talus blocks now form a 3-foot wide spine of broken blocks with don't-look-down drops to either side—and we've just barely gotten started.

Place your hands and feet carefully here.

This section makes for a few good wide-eyed scare-the-wife photos, reinforcing the reality that we're no longer scrambling—we're climbing now.

While it's an intense section of the ridge, it's also short-lived.

A hidden saddle materializes, providing a moment's respite, as well as a terrific perch from which to contemplate imminent challenges ahead.

My companions, who by now are quite reasonably wondering just what the heck I've gotten them into, begin asking me what lies ahead.

Given potentially delicate psyches, this is a tricky question, which I answer with a reassuring barrage of ambiguities.

Staring us in the face now is a section of slabs.

To the left, of course, is The Void, and we won't be going there.

However, to the right is also The Void, and we must now traverse smooth granite slabs above it which roll off to infinity in just the right way to evoke maximum menace.

But do not despair!

Cautious footwork ahead reveals a generous crack system that morphs into a bona-fide escalator, speeding nervous climbers upward in relative safety. To our left is a reassuring wall of granite which safely shields our eyes from sights of frights. This pattern, which repeats throughout the East Ridge route, does indeed delight the heart of a mountaineer:

The terrain presents a terrifying mixture of exposure and seemingly-impassible granite, only to reveal at the last moment a reasonable passage across.

In this manner, the East Ridge does manage to just eke out a deserved Class 3 rating—though the massive exposure and accompanying anxiety will surely make it feel otherwise. But perhaps we're making that assessment a little early. Coming up fast on the horizon are a few more surprises...

Embracing Exposure

Russell's East Ridge may be the easiest route to the peak's summit—but that doesn't mean it's easy (Secor's assessment notwithstanding).

We now reach the meat of the climb. The ridge narrows and the exposure sharpens. Our elevation— just under 14,000'—is also making itself known, fueling both exhaustion and paranoia. The ridge's narrowness permits unobstructed views of the abyss directly to our south. It's been there all along, of course, but until now the drop has been hidden.

Faced with thousand-foot drops off each shoulder, the brain struggles to make sense of this vertically-oriented landscape.

Consequently, our sense of balance is impaired, putting a slight totter in our steps.

Meanwhile I scramble about, camera in hand, like a photographically-inclined mad scientist, looking to capture the best possible angle.

The climbing here is occasionally tricky, though not exactly difficult.

There are bold steps to be taken, a reach for a hold here and there, blocks to scale or bypass.

All of these moves happen in close if not exactly dire proximity to huge expanses of open air, which certainly keep the pulse racing.

Puffy clouds have sprouted up above several nearby summits, white against the brilliant blue of the Sierra sky. The clouds will bear watching, though as yet they hold no threat.

Meanwhile, my companions Bob and father Hugh seem simultaneously impressed with the spectacle of this marvelous ridge—and eager to leave it for solid ground.

I can't blame them. The East Ridge makes for an overwhelming experience, as inspiring views swirl with ever-present dangers. Should we be elated or terrified? Or both, simultaneously?

The crux of the route arrives: a traverse astride the very top of the ridge, which narrows to a two or three foot wide block of talus. Certainly, our nervous systems will be jangling for a while when this adventure is over.

We cautiously continue past this narrow section, which in truth marks the end of the East Ridge. Mt. Russell's east summit is now less than a hundred yards distant. A few tricky sections of climbing remain ahead, but these are unrelated to the ridge.

Ahead, we have only to scramble up a short, broken headwall to gain Russell's lower, eastern summit. A short way beyond that (plus a menacing little traverse which we'll keep secret for now) and we'll be atop the mountain for good.

Near Russell's summit, with Mount Whitney beyond

Two Summits

Given the considerable energy—both mental and physical—we've expended to get this far, it would be nice if all the difficulties were past. This, of course, is not the case.

Mount Russell has two summits, east and west. To get to the higher west summit, we must travel yet another exposed ridge. Unlike the somewhat-friendly East Ridge, this short but savage little summit traverse demands a bit of extra caution.

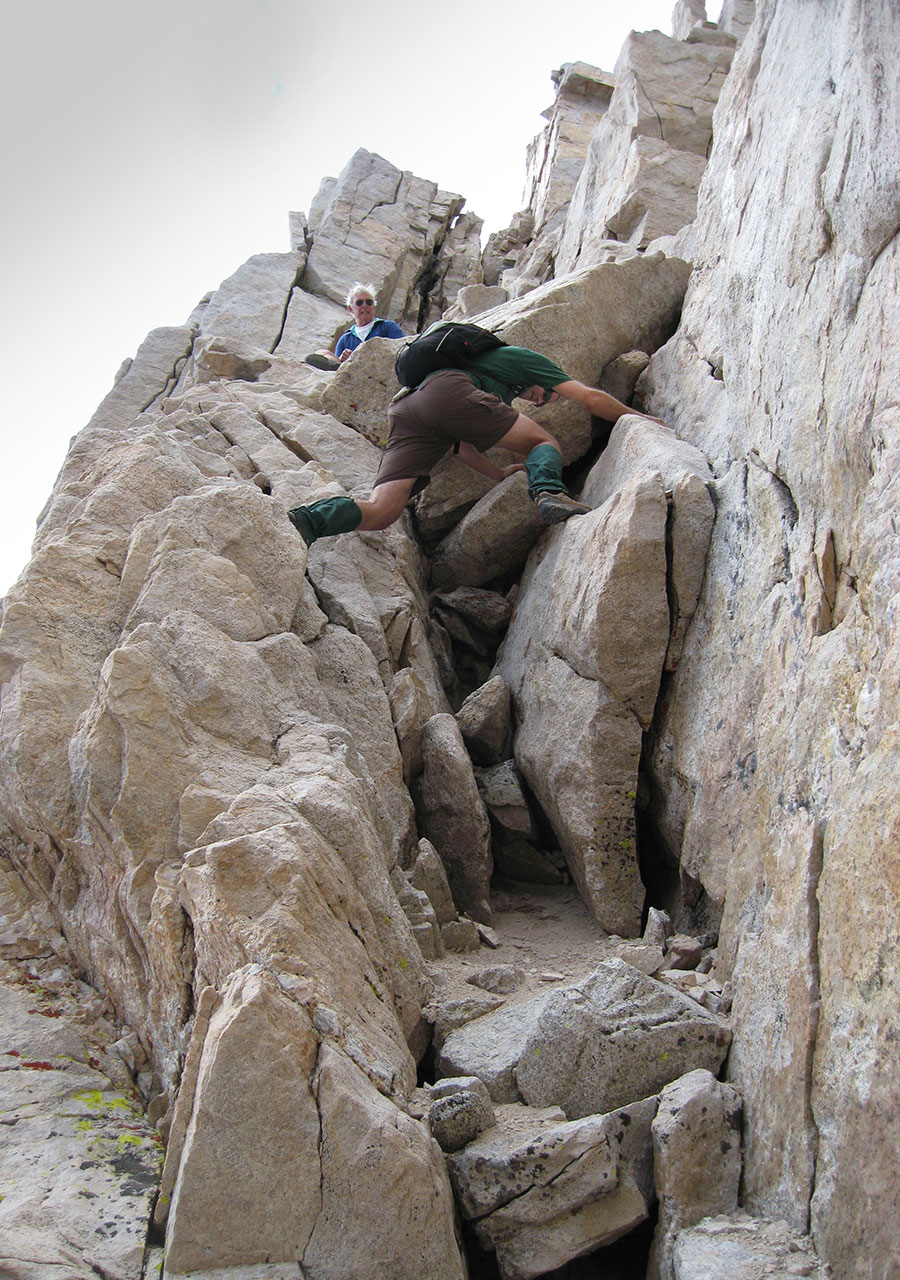

Finishing up the last of the East Ridge Route, we make quick work of the east summit's headwall.

Just like that, we're standing atop the East Summit, basking in 14,000-foot Sierra sunshine.

The view to the south is dominated by Mount Whitney, whose North Face towers nearly five hundred feet higher.

We will head south toward Whitney and Iceberg Col for our descent today, making a grand loop, but first we must reach Russell's true summit to the west.

And so, on to the not-quite-last of today's technical challenges: the summit ridge traverse.

Remaining topside on this narrow, exposed ridge requires one to execute a few high-pressure moves at one troublesome block in particular.

As an alternative, it is possible to scramble down and to the north, onto Russell's North Face, traversing ledges until you've passed the problematic block.

This is the option we choose. Aside from a few modest route finding challenges, it presents only modest difficulties—though, as you may have guessed, the relative sense of exposure remains high.

In the lead, I traverse a bit west of the true summit, then backtrack up, climbing easy rock to find myself on top of Mount Russell at last.

Bob and Hugh aren't far behind. We congratulate each other on a successful summit. Speaking of summits, Russell's apex is little more than a small pile of granite blocks overlooking the sheer south face. Just beyond that lip of rock lie a few of the Sierra's best rock climbs, including the Fishhook Arete and the Mithril Dihedral.

We rest, briefly, atop the summit, enjoying the views. It would be nice to stretch out on these warm, sunny blocks of granite and take a quick nap, as the combination of exposure, altitude, and effort has clearly taken its toll on all of us. But our fatigue, plus the ever-darkening clouds, is all the more reason not to linger.

I suggest that now is the time to resume our journey, and off we go, repeating the North Face traverse in reverse to get back to the saddle between East and West summits—and the last (hopefully!) of the day's technical challenges.

South Face Downclimb

Along with the East Ridge, Mount Russell's South Face-Right Side is one of the few Class 3 climbing routes on the mountain. The operative word being climbing, of course.

If you're used to interpreting Class 3 rock as scrambling, you'll find the South Face takes the already stretched Class 3 designation of the East Ridge and bumps it further a notch or two. Well, my friend Bob observes, At least the handholds look good.

When I down-climbed the South Face for the first time (on my earlier solo venture), I was stopped by two climbers who'd just ascended the Fishhook Arete.

They'd been unsuccessfully scouting the South Face-Right Side from above, and wondered if I knew where the Class 3 downclimb was.

I didn't, but I at least knew where the downclimb was supposed to be.

I'd memorized a few features from photographs before my climb.

Nonetheless, the route we ended up choosing felt a lot like Class 4 work—an unwelcome finish to an already difficult day.

The South Face-Right Side's difficulties are concentrated at the ridgeline, where climbers must ascend (or descend) a 60-90' headwall.

Much of this imposing feature is exposed, technical rock.

Since I'm now leading my two friends, I've put more effort into ferreting out that elusive Class 3 passage (though in truth I have my doubts about its existence).

The key seems to be finding a chimney that drops diagonally from the west side of the headwall—staying a few yards away from the headwall itself.

R.J. Secor notes that the headwall can also be passed via the chimneys to the east, though these routes may be no better.

Any way you slice it, getting down involves a solid 80 feet or so of near-vertical climbing, good hand-holds or not.

When we finally reach the giant talus field below, it's time to breath a huge sigh of relief.

This is the first safe ground we've stood upon in hours.

Aside from the short headwall section, the remainder of the South Face is just one big scree slide, so out come the trekking poles.

Climbers have noted that ascending Russell's steep, loose South Face can be quite tedious.

It's not much fun going down, either. Trekking poles can be of great assistance here, as they allow you to transfer weight off already-protesting legs. Additionally, the poles make it easier to keep your body mass forward, preventing a nasty backwards fall when your feet suddenly slide out from under you.

Down, down, down we go.

Though it's not much good for my morale, I can't help thinking about the 6000 vertical feet we must descend to reach the car. Also popping up now is an altitude-spawned headache, and a tinge of accompanying nausea. Both will vanish once we reach Lone Pine—but that's a long way away.

Our resident astro-geologist lightens the mood by demonstrating how to generate long-traveling echoes. With the proper vocal modulation, he succeeds in getting an echo off Mt. Whitney's north face—quite a nifty feat, proving that science does indeed have occasional practical value. Meanwhile, I'm eyeing the various notches along the Whitney-Russell saddle below, trying to guess which one will lead us to Iceberg Lake with the fewest possible complications.

Mount Russell's south face from Iceberg Col

Iceberg Col

The clouds continue to darken as we descend, the temperature drops, and a few actual snowflakes drift about. The sky seems to lack the necessary ingredients to produce lightning.

The cloud cover is therefore a welcome development—though I would not want to be atop any ridges. Our target now is Iceberg Lake, via Iceberg Col. The Col is easy to miss compared to the obvious (and incorrect) notch between Whitney and Russell, which leads to big-time cliff trouble.

Luckily for my companions, I've already made that mistake a few weeks earlier, so I lead our group to the proper pass just as the snow starts in earnest.

Snow?

Sure enough, snow it is, a little Sierra September surprise.

We scramble to pull hats and jackets out of our packs as the little white flakes swarm about with sudden intensity.

The novelty of snow seems to put a little bounce in all our steps as we hike down a little use trail leading toward the blue waters of Iceberg Lake below.

Our elevation soon drops below the magic line, and the snow turns to rain, trading novelty for nuisance.

Still, it's good to have a little weather to roughen up the edges of our adventure—and lightning remains conspicuously absent, which is just how I like it.

There will be no hair-raising tales of static today, thank goodness!

The short scree slope below Iceberg Lake proves amenable, and we soon reach the lake, elevation 12,700'.

Here, it's time to pump water to refresh our bottles.

Wet and exhausted, it doesn't take long for our bodies to cool, cutting snack time short.

Iceberg Lake, of course, is a popular (if lofty) campsite for climbers attempting Mount Whitney's Mountaineer's Route.

We're borrowing the lower portion of the Mountaineer's Route as part of our loop through the Whitney Zone. Now, back on the trail, we shuffle past tents, campsites, and weary hikers. For us, all the major climbing is over. We just have to slog down another four thousand vertical or so, and then we get to call it a day.

A weary author

Hiking Out

I find hiking down among the hardest tasks in mountaineering. Yes, it's easier to go down (usually!), but the exciting work is done, and now comes the tedium and suffering.

It takes a great deal of concentration to hike down, trying to pay attention to placing each foot on good ground, trying to forget how much each foot protests. We can see our destination far, far below, a vertical mile guaranteed to induce despair.

On the chutes below Iceberg Lake, Bob slips and twists his back. Meanwhile, my headache has continued to blossom, putting a persistent, get-it-over-with grimace on my face. In contrast, our scientist seems to have found his second wind. He eagerly points out nearby features of geological interest (interesting to him, at least), and shows no sign of slowing down.

I am glad to have the company of this quirky father-son duo. There are advantages to traveling solo, but sharing adventures with close friends surely trumps them all.

Days like these are precious. It is rare enough that my friend Bob and I see other at all, given the distance that separates us. To be here together in the beautiful Eastern Sierra is a fine treat, indeed.

With a little help from Dad, Bob is back on his feet, and we resume hiking downward. To amuse ourselves, we begin speculating about what shape we'll be in tomorrow. Too sore to walk?

Bob notes that we'll have to wait 48 hours, as that seems to be when muscle soreness peaks. I don't know that I'll set any personal bests in that department, but my own legs are certainly tired. In any case, a big salute must be given to our senior climber, Hugh, who has survived this day in fine form and remains—at least for the moment—fully ambulatory.

At Upper Boy Scout Lake, I stop to tape up my feet and dry my socks—a little preventative medicine for the remaining few miles. My companions press on. I'll catch up soon enough. As father and son pass slowly out of sight, laughing and joking, I feel a great moment of satisfaction in having orchestrated this little adventure.

Perhaps, someday, it will be a much-older me hiking down with my son, talking excitedly about the rigors of Russell's East Ridge, the unexpected snow, that South Face Headwall downclimb. I hope so. For now, I lace up my shoes, take a drink of water, and hit the trail to keep from falling too far behind.